MIAMI – The NFL Players Association is investigating the relationship between agent Drew Rosenhaus and a former financial adviser who persuaded a number of players to invest in a failed Alabama bingo casino, a source with knowledge of the inquiry told Yahoo! Sports.

According to multiple sources who talked to Y! Sports on the record and for background, Rosenhaus and Jeff Rubin had an unusually close business relationship that spanned upwards of seven years. That relationship might have resulted in Rosenhaus breaching the fiduciary duties all agents who are certified by the NFLPA owe to their clients. The relationship has been scrutinized in part because of a series of issues surrounding Rubin, who is at the center of a bankruptcy filing for the failed casino that cost the players as much as $43.6 million.

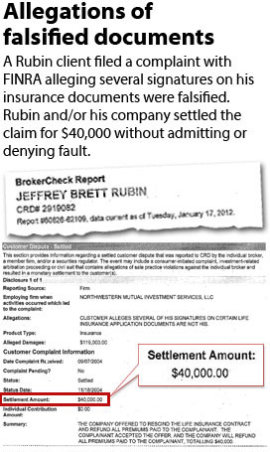

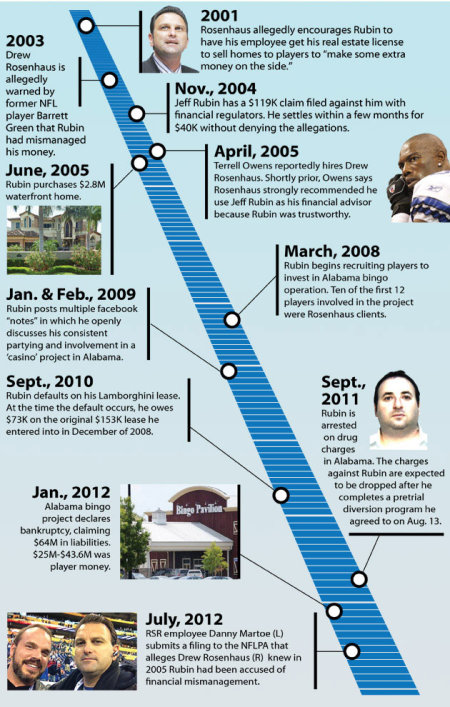

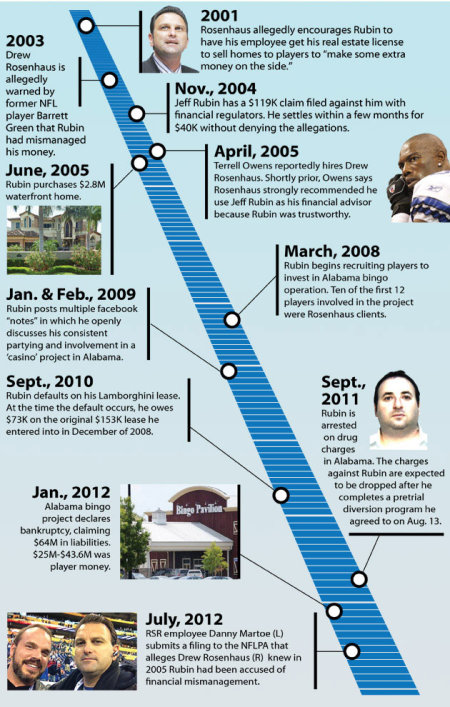

Starting in 2003, Rubin was questioned about financial transactions that could have raised red flags for a financial adviser, a five-month Y! Sports investigation has found. That included allegedly mismanaging a player's game checks in 2003 and settling an issue related to allegedly falsified insurance documents in 2004.

The NFLPA is looking into whether Rosenhaus should have paid closer attention and kept his clients away from Rubin, founder of Pro Sports Financial. Multiple sources, including free agent NFL wide receiver Terrell Owens, indicate Rosenhaus actively recruited players with Rubin and valued that association because it helped him increase his business. Although Rosenhaus specifically denied any relationship to the casino and there is no evidence to indicate he profited in any way from the project, his client base grew to more than 100 players during the seven years Rosenhaus and Rubin were associated. Rosenhaus currently represents about 140 players, more than any other agent in the NFL.

If Rosenhaus is found to have violated NFLPA regulations on agent conduct, he could be subject to discipline by the union.

According to two sports law specialists, including a lawyer who represented Rosenhaus, agents have a high standard of responsibility when it comes to a player's off-the-field affairs.

Attorney Darren Heitner, who represented Rosenhaus in a fee collection matter against former Rosenhaus client Bryant McKinnie that has been privately settled, explained those responsibilities in an April 2010 article in the Dartmouth Law Journal: "A sports agent has a duty to discover and disclose to his clients material information that is reasonably obtainable, unless the information is so clearly obvious and apparent to the athlete that, as a matter of law, the sports agent would not be negligent in failing to disclose it. … Athletes are not always aware of all events concerning their affairs outside of the field of play, and rely on their agents to provide assistance when necessary, including the disclosure of all information holding importance for the athletes."

One of the country's eminent sports law scholars, Timothy Davis of the Wake Forest University School of Law, agreed with Heitner's statement on the duty agents owe to their clients.

"A fiduciary [agent] is one who acts primarily for the benefit of another," Davis said. "As such, one obligation imposed on the fiduciary is that he or she inform the principal [player] of all matters that may affect the principal's interests."

Eighteen of Rosenhaus' player clients invested in the failed Alabama bingo casino that declared bankruptcy earlier this year. Rubin helped encourage 35 athletes, some of whom were Rosenhaus' most notable clients, to invest in the Dothan, Ala., bingo operation that was raided and subsequently shut down.

Multiple sources say at least $25 million of the $68 million the gambling operation claims to have lost has been identified as player money. Bankruptcy filings indicate that figure could be as high as $43.6 million for all the players, including those not represented by Rosenhaus. Among the 18 Rosenhaus clients who invested in the bingo project were Jevon Kearse, Fred Taylor, Frank Gore, Plaxico Burress, and Owens. Owens has since fired Rosenhaus.

Another Rosenhaus client, Roscoe Parrish, is the only player Y! Sports confirmed has directly sued Rubin in connection to the casino matter. Multiple sources indicated that other players have instead filed lawsuits against law firm Greenberg Traurig, which allegedly set up investment vehicles for the players. The players are suing Greenberg Traurig because they believe that legal strategy gives them the best opportunity to recover the money they lost.

While other high-profile agents represented players who invested in the Alabama project – David Dunn and Joel Segal represent four players each – Rosenhaus is the only one who appears to have had an extensive recruiting and referral relationship with Rubin. At one time or another, Rosenhaus and Rubin shared at least 26 clients.

In wide-ranging discussions with more than 39 sources – including former Rubin employees, current and former players, attorneys, financial professionals, agents, and recruiters – questions regarding the nature and extent of Rosenhaus' relationship with Rubin were raised.

Rubin declined to comment for this story on at least 10 occasions through attorneys, relatives, and friends.

In a three-hour interview with Y! Sports in Miami in July and another one-hour phone interview in August, Rosenhaus and his brother Jason – who works for Rosenhaus Sports Representation and is also an NFLPA certified agent as well as an attorney and CPA, – both denied having a recruiting and referral relationship with Rubin. The brothers also denied any knowledge of Rubin's unscrupulous behavior prior to the bingo operation beginning to unravel in or around 2010.

"Let me say this on the record, I had no reason to believe that Jeff Rubin was doing anything illegal or irresponsible or unethical," Drew Rosenhaus said. "We never had any inkling that he was ever dishonest. We never had a player come to us until this casino fell apart."

However, legal documents obtained by Y! Sports as well as interviews with multiple sources show Rosenhaus could have had reason to know Rubin , who graduated from the University of Florida with a degree in exercise and sport sciences in 1997 and began developing a relationship with Rosenhaus in 1999, had mismanaged client money as early as '03 – approximately five years before Rubin began recruiting players to invest in the bingo operation.

In an arbitration document filed with the NFLPA against Rosenhaus by attorney David Cornwell, suspended Rosenhaus Sports vice president Danny Martoe alleged he and former Rosenhaus client Barrett Green told Rosenhaus "in or around 2005" that Rubin had mismanaged Green's funds.

Green, an NFL linebacker for six years, confirmed Martoe's account when contacted by Y! Sports but said he and Martoe told Rosenhaus about Rubin's mismanagement two years earlier during his first contract with the Detroit Lions. Green said he hired Martoe to investigate why money was missing from his account. That investigation, two sources said, revealed the unauthorized transfer of two of Green's game checks into the account of two other players Rubin represented.

In the filing, Martoe said Green considered firing Rosenhaus for referring him to Rubin and telling the player Rubin was "trustworthy and competent."

Because Rosenhaus feared being fired by Green, he and Martoe discussed "the manner in which [Rubin] mismanaged Mr. Green's account" on multiple occasions, according to the filing. It was during those discussions Martoe said Rosenhaus "became impressed" with him and "encouraged [him] to come work with Rosenhaus Sports."

Martoe accepted Rosenhaus' offer and went to work for Rosenhaus Sports in or around 2005. Martoe now claims the firm owes him more than $1 million in commission and compensatory damages.

According to Martoe's claim, shortly after he joined Rosenhaus Sports, Rosenhaus directed him to "repair his relationship with [Rubin]," who had become "dissatisfied" with Martoe after he was fired by Green. Rosenhaus did so because Rubin, according to Martoe's filing, was "'very important to Rosenhaus Sports business."

Martoe objected to Rosenhaus' instruction, telling the agent he "did not trust Mr. Rubin," according to the filing.

Martoe declined further comment, Cornwell said.

Beyond the situation with Green, Rubin settled a claim for $40,000 in 2004 when one of his clients alleged several signatures on insurance documents executed in his name were not his. That claim – which Rubin did not deny – and the settlement are listed on the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority website.

Four years later, Rubin began recruiting players to invest in the failed Alabama bingo operation – an operation that was $41 million in debt when Rubin secured his first 12 NFL investors, according to investment documents obtained by Y! Sports. Ten of those initial investors were Rosenhaus clients.

Recruiting relationship in action

In early 2005, Owens was at the height of his career. He had just appeared in the Super Bowl with the Philadelphia Eagles and was a perennial Pro Bowler. Despite the success, he was in search of a new agent after deciding to fire agent David Joseph, who represented him for the first nine years of his career.

The decision wasn't one Owens took lightly.

Owens, who lost $2 million in the Alabama casino operation, described the rationale behind the split from Joseph in his self-titled book "T.O." The wide receiver said it was ultimately a review of his financial affairs that led him to believe he needed new representation.

When Owens and his friend of nearly 20 years, Theron Cooper, saw Rosenhaus walk into a celebrity bowling tournament in Miami, Owens said in the book he felt "fate was intervening." Owens urged Cooper to approach Rosenhaus to see if he'd be interested in representing the wide receiver.

After Cooper initiated a brief discussion between Rosenhaus and Owens, the parties agreed to have a formal meeting in Atlanta. It was at that meeting in a downtown Atlanta hotel that Owens and Cooper said Rosenhaus introduced them to Rubin, who they said Rosenhaus brought to the meeting unannounced. Former Rubin employee Peggy Lee confirmed that she attended the meeting with Rubin.

Owens and Cooper described a "joint presentation" between Rosenhaus and Rubin which was attended by multiple members of Rosenhaus' and Rubin's teams and lasted a little more than an hour. Both Owens and Cooper remember Rosenhaus emphatically endorsing Rubin to handle Owens' financial affairs.

"Drew said, 'If you're looking for a financial adviser, I recommend Jeff Rubin and Pro Sports Financial,' " Cooper told Y! Sports. "He told Terrell and I that he had referred a lot of his players to Rubin."

According to Owens, in a follow-up meeting at the wide receiver's Atlanta-area home a few days later between himself, Cooper, Rosenhaus and Rosenhaus employee Robert Bailey, Rosenhaus again urged Owens to hire Rubin.

"We recommend you use Jeff," Owens recalls Rosenhaus saying. "He handles our clients, we trust him."

When asked if Owens' recollection of how he met and began to work with Rubin was accurate, Rosenhaus declined comment. However, Rosenhaus was adamant that simultaneous meetings between himself, a financial adviser, and a player would not constitute cooperative recruiting. He was also adamant that he and his company don't endorse financial advisers to players.

But Owens said not only did Rosenhaus and Rubin cooperatively recruit him, Owens says he never would have signed with Rubin had it not been for Rosenhaus' repeated assurances that Rubin was the right man to handle Owens' financial affairs.

"I never knew who Jeff Rubin was before Drew introduced me to him," Owens said. "Drew was supposed to be the best agent, he's recommending Pro Sports Financial and they represent [a large number] of Rosenhaus clients, you think they must be the best too. Why wouldn't you want to go with the best?"

When asked if he felt that Rosenhaus shared in the responsibility for the losses players experienced with Rubin, Owens offered a measured response.

"Some of this is my fault because I had ultimate responsibility for my finances," said Owens, who was released by the Seattle Seahawks last week. "As a player without much understanding of the financial realm, we're easy prey. … How do you decipher who's good and who's bad?

"[But] with what I know now, Drew definitely needs to share in the responsibility. … Other players may not want to speak up out of loyalty to Drew but at the end of the day he bears some of the responsibility [for our losses] based on the referrals he was giving to [Rubin] and Pro Sports Financial.

"For someone to work as hard for their money as we do, to have it taken away by people we trust, who we find out later had other motives, it's a sick feeling."

Getting ahead and staying ahead

An NFL veteran player who spoke to Y! Sports on the condition of anonymity, said he was recruited simultaneously by Rosenhaus' and Rubin's companies in or around 2006, and that the firms had a cooperative recruiting relationship until at least 2008. The player was among those who lost money in the Alabama casino operation.

"[A Rosenhaus employee] came to see me and [a Rubin employee] was on the trip with him. They recruited together," the player said. A former Rubin employee confirmed the firms recruited prospective clients together during this time and that the direction to do so came from firm management.

"I would have loved to have known all the shady stuff that was going on with Jeff Rubin," the veteran player said. "That information would have changed things dramatically [in terms of allowing Rubin to manage my finances]. … To find this stuff out after the fact is disheartening. And that's part of the reason I fired Drew, because I had to question if he had my best interests in mind."

When asked about the player's claims, Rosenhaus said neither he nor anyone at his firm ever cooperatively recruited a prospective client with a financial adviser to the best of his knowledge.

"Not that I know of," Rosenhaus said.

Rosenhaus said agents and financial advisers are sometimes forced to meet with a player simultaneously in the recruiting process. Of five other agents surveyed, only one said he had ever experienced anything like that.

When asked if a player could construe a shared meeting as an endorsement by one party of the other, Jason Rosenhaus said: "The answer is no." Asked if Rosenhaus Sports' company policy allowed employees to communicate with financial advisers and if there were any parameters that governed those interactions, Drew Rosenhaus said his employees were allowed to communicate with financial advisers so long as they did not violate NFLPA regulations.

"We obviously expect them to operate at the same level that we do, and to the best of our knowledge they do, otherwise they wouldn't be working for us," Rosenhaus said.

When asked how a Rosenhaus employee and a Rubin employee could have ended up in front of a college player at the same time and leave the player with the impression they were collaboratively recruiting, Rosenhaus said it was likely a misunderstanding.

"We recruit so many players and take so many trips," Rosenhaus said. "Maybe guys are on the same flights coincidentally, or went to similar games and communicated with a financial adviser at a game."

But the player said the two firm's employees coming to see him at the same time was no coincidence. A Rosenhaus employee, the player said, "is the one who got me in touch with the guys at [Rubin's company,] Pro Sports Financial." He said he believed Rosenhaus was well aware of the arrangement.

"It's all about getting ahead and staying ahead for Drew … [he] definitely had to know what was going on," the player said. "Out of sight, out of mind, I guess. It was, 'Do what you've got to do to get the kid signed,' and Drew will do whatever it takes to sign players."

Warning signs

Aside from the allegations by Green and Martoe, Y! Sports identified numerous instances beginning in 2004 where accessible information – which didn't require consent or approval to uncover – might have provided material warning signs about Rubin's inability to safely manage his clients' finances.

September 2004 – A $119,000 complaint was filed against Rubin with FINRA by former NFL linebacker Johnny Rutledge. Rutledge alleged "several of his signatures on certain life insurance application documents [were] not his."

According to BrokerCheck – which is publicly available on the FINRA website and requires less than five minutes to access – Rubin and/or his firm settled the claim for $40,000 shortly after it was filed. They did so without either admitting or denying the allegations.

When asked if he was aware of this complaint against Rubin, Drew Rosenhaus said, "[T]his is the first I've ever heard of that."

• June 2005 – Rubin, 31 at the time, purchased a custom waterfront home in South Florida for $2.8 million. The home was in an area where at least four of Rubin’s clients also lived. He leased a Lamborghini for approximately $153,000 in 2008 and defaulted on the agreement in 2010. One former Rubin employee said Rubin was making upwards of $500,000 a year by '05.

"Your financial adviser shouldn't be living in the same neighborhood as his multimillion-dollar-earning clients," said Eric Pettus, a financial adviser who is working with former Rubin client Samari Rolle. "Even if he has a hundred clients, the percentage he should be making doesn't make him enough to be living in a new house in Lighthouse Point."

Mike McIntyre, a former Pro Sports Financial vice president of client services and longtime friend of Rubin's, said Rubin began leveraging clients for personal gain as early as 2001. In one instance, McIntyre says Rubin did so at Rosenhaus' suggestion.

"Back in the day, the company wasn't making that much money," McIntyre said in a June discussion with Y! Sports. "And … we were working a lot with Drew [who] really took a liking to me … [he] was like 'Mac, I want you to make more money. … 'You know what, I got this guy who's buying a house. Why don't you let Mac become a [real estate agent], have him get his real estate license? This way he can get a real office guy, make some extra money on the side. It doesn't take that much commitment and time to do both."

Rubin and McIntyre acted on Rosenhaus' suggestion and according to the Florida Department of Business Professional Regulation, McIntyre became officially licensed to sell real estate in April 2001.

"The way Jeff got his house is [through] Michael Friend, who was the builder in Lighthouse Point," McIntyre said. "[Friend] built Jevon's house and he built [Plaxico Burress'] house. So they kinda worked out a deal where commissions for those two houses brought down the price for Jeff's house."

Current Washington Redskins player Santana Moss and recently retired Redskins player Clinton Portis also bought homes from Friend, according to McIntyre. All four players purchased their homes between September 2005 and March 2006. Only Kearse still lives in his home full time. Burress' home was subject to foreclosure proceedings in 2010, and Moss and Portis left their homes, taking multimillion dollar losses.

An agent's primary responsibility

The NFLPA requires agents to act at all times in a fiduciary capacity on behalf of their clients to protect their best interests.

Timothy Davis, who co-authored the book "The Business of Sports Agents" with former NFLPA arbitrator Kenneth Shropshire, said, "[T]he relationship between an athlete and a sports agent is governed by the same legal principles as any other agent and principal relationship. The basic obligations that agents owe to their clients are defined not only by their contract but by the fiduciary characteristics of the relationship. As is true of other agency relationships, the agent and athlete relationship is subject to the duties that arise from the fiduciary duties imposed on the agent. The most fundamental fiduciary obligations imposed on the agent are the duties of undivided loyalty and good faith.

"Although fiduciary duties arise by operation of law, player association agent regulations acknowledge the fiduciary character of the relationship. For example, both the NFLPA and MLBPA agent regulations refer to the fiduciary character of the player/agent relationship."

When Rosenhaus and his brother Jason were asked if fiduciary duty required them to put the interests of their clients above their own they stated it did, at all times.

"Everything you do on behalf of your client, you've got to put their interests before what your own would be," Rosenhaus said. "We've always subscribed to that."

But numerous financial professionals who have worked with Rosenhaus and spoke with Y! Sports on the condition of anonymity said Rosenhaus and his employees consistently refused to make referrals to financial advisers who would not send them business in return. This practice continued long after it should have been clear that the reciprocal referral relationship they had with Rubin and his company had exposed their clients to risk.

"Drew's employees have said to me, 'Drew likes you, he thinks you do great work for the players, but he said we can't refer business to you because you don't refer business to us,' " one of the financial professionals said.

Another well-placed financial source said "I asked [a Rosenhaus sports employee] how come they don't refer clients to me and their response was 'because you don't recruit.' The inference was they wouldn't send me players because I didn't recruit to send players their way."

The Rosenhaus brothers declined to comment when asked if the financial professionals' claims were true.

In his arbitration filing with the NFLPA, Martoe said Rosenhaus sought more than a reciprocal referral relationship with some of the financial advisers they introduced to players. Martoe alleged he was told that if he introduced clients "like Dez Bryant and others" to a financial adviser at SunTrust bank, he would receive his commissions faster. That's because Rosenhaus' firm would get a "bigger loan and a better rate" from SunTrust, Martoe said.

While the Rosenhaus brothers declined to comment on whether they had ever referred a player to a specific financial adviser, citing the confidentiality of the NFLPA arbitration process, Drew Rosenhaus acknowledged they had given some players "a couple of names of guys that we think could possibly do a decent job for them."

When asked if referring a player to those financial advisers subjected them to a duty to investigate an adviser's credentials, Jason Rosenhaus said "the short answer is 'yes,' to a reasonable extent." When asked to define what "reasonable" efforts they would take to vet an adviser when making a referral, Jason Rosenhaus said it was "impossible" to do as "everything depends on a particular circumstance."

"I think that obviously it should be somebody that's registered with the NFLPA in good standing and who our clients speak highly of," Drew Rosenhaus said. "If our clients are happy with a financial adviser, that speaks well of [him]."

Asked if NFLPA registration was an endorsement of an adviser's skill, honesty or competence, the Rosenhaus brothers said it was not, it was merely a "minimum qualification." When asked if they were making "reasonable" efforts to refer clients to honest, ethical, and competent advisers by relying solely upon the "minimum qualification" of NFLPA registration and their clients' willingness to "speak well" of a given adviser, Drew Rosenhaus said "The biggest problem is, you can do a bunch of research on a financial planner, [he] could have great recommendations from players …. could be in good standing and then [he] goes off and does something … out of character. ....Anytime you recommend someone, that's a tough thing. I make sure to tell guys that I can't vouch for anybody but myself and Jason."

The NFLPA declined to comment on whether Rubin was ever registered in the NFLPA financial adviser program.

Asked if there was a heightened duty to conduct periodic due diligence on an adviser like Rubin who represented such a large number of Rosenhaus clients, the brothers said they were prohibited from doing so. It's unclear what rule or regulation they were citing as authority.

"Once a player has a relationship with a financial adviser, at that point, unless a player asks us to get involved, asks us to evaluate their financial investments, we can't," Drew Rosenhaus said. "There's nothing that we can do."

While the Rosenhauses reject the suggestion they shared in the responsibility for the losses their clients experienced in dealing with Jeff Rubin, they did shed some light on why they may have missed so many seemingly discoverable issues.

The Rosenhaus brothers didn't want to be fired.

"As long as [Rubin] didn't say to the guys we had with him, 'fire Drew,' we peacefully co-existed," said Jason Rosenhaus. "Our clients were mesmerized by this guy."

Asked if their concern for appeasing clients may have impacted their ability to represent the players' best interests, the Rosenhauses said they were as surprised as anyone by Rubin's fall.

"It's not something where we looked the other way and we knew what was going on," Jason Rosenhaus said. "We were shocked. Everybody was shocked."

"I guess the point I would make to you is … there are people who have to pay for this, and there are people who should be punished for it," Drew Rosenhaus said. "There are people who should be accountable, but Jason [Rosenhaus] and I are innocent victims, just like our clients."

According to multiple sources who talked to Y! Sports on the record and for background, Rosenhaus and Jeff Rubin had an unusually close business relationship that spanned upwards of seven years. That relationship might have resulted in Rosenhaus breaching the fiduciary duties all agents who are certified by the NFLPA owe to their clients. The relationship has been scrutinized in part because of a series of issues surrounding Rubin, who is at the center of a bankruptcy filing for the failed casino that cost the players as much as $43.6 million.

Starting in 2003, Rubin was questioned about financial transactions that could have raised red flags for a financial adviser, a five-month Y! Sports investigation has found. That included allegedly mismanaging a player's game checks in 2003 and settling an issue related to allegedly falsified insurance documents in 2004.

The NFLPA is looking into whether Rosenhaus should have paid closer attention and kept his clients away from Rubin, founder of Pro Sports Financial. Multiple sources, including free agent NFL wide receiver Terrell Owens, indicate Rosenhaus actively recruited players with Rubin and valued that association because it helped him increase his business. Although Rosenhaus specifically denied any relationship to the casino and there is no evidence to indicate he profited in any way from the project, his client base grew to more than 100 players during the seven years Rosenhaus and Rubin were associated. Rosenhaus currently represents about 140 players, more than any other agent in the NFL.

If Rosenhaus is found to have violated NFLPA regulations on agent conduct, he could be subject to discipline by the union.

According to two sports law specialists, including a lawyer who represented Rosenhaus, agents have a high standard of responsibility when it comes to a player's off-the-field affairs.

Attorney Darren Heitner, who represented Rosenhaus in a fee collection matter against former Rosenhaus client Bryant McKinnie that has been privately settled, explained those responsibilities in an April 2010 article in the Dartmouth Law Journal: "A sports agent has a duty to discover and disclose to his clients material information that is reasonably obtainable, unless the information is so clearly obvious and apparent to the athlete that, as a matter of law, the sports agent would not be negligent in failing to disclose it. … Athletes are not always aware of all events concerning their affairs outside of the field of play, and rely on their agents to provide assistance when necessary, including the disclosure of all information holding importance for the athletes."

One of the country's eminent sports law scholars, Timothy Davis of the Wake Forest University School of Law, agreed with Heitner's statement on the duty agents owe to their clients.

"A fiduciary [agent] is one who acts primarily for the benefit of another," Davis said. "As such, one obligation imposed on the fiduciary is that he or she inform the principal [player] of all matters that may affect the principal's interests."

Eighteen of Rosenhaus' player clients invested in the failed Alabama bingo casino that declared bankruptcy earlier this year. Rubin helped encourage 35 athletes, some of whom were Rosenhaus' most notable clients, to invest in the Dothan, Ala., bingo operation that was raided and subsequently shut down.

Multiple sources say at least $25 million of the $68 million the gambling operation claims to have lost has been identified as player money. Bankruptcy filings indicate that figure could be as high as $43.6 million for all the players, including those not represented by Rosenhaus. Among the 18 Rosenhaus clients who invested in the bingo project were Jevon Kearse, Fred Taylor, Frank Gore, Plaxico Burress, and Owens. Owens has since fired Rosenhaus.

Another Rosenhaus client, Roscoe Parrish, is the only player Y! Sports confirmed has directly sued Rubin in connection to the casino matter. Multiple sources indicated that other players have instead filed lawsuits against law firm Greenberg Traurig, which allegedly set up investment vehicles for the players. The players are suing Greenberg Traurig because they believe that legal strategy gives them the best opportunity to recover the money they lost.

While other high-profile agents represented players who invested in the Alabama project – David Dunn and Joel Segal represent four players each – Rosenhaus is the only one who appears to have had an extensive recruiting and referral relationship with Rubin. At one time or another, Rosenhaus and Rubin shared at least 26 clients.

In wide-ranging discussions with more than 39 sources – including former Rubin employees, current and former players, attorneys, financial professionals, agents, and recruiters – questions regarding the nature and extent of Rosenhaus' relationship with Rubin were raised.

Rubin declined to comment for this story on at least 10 occasions through attorneys, relatives, and friends.

In a three-hour interview with Y! Sports in Miami in July and another one-hour phone interview in August, Rosenhaus and his brother Jason – who works for Rosenhaus Sports Representation and is also an NFLPA certified agent as well as an attorney and CPA, – both denied having a recruiting and referral relationship with Rubin. The brothers also denied any knowledge of Rubin's unscrupulous behavior prior to the bingo operation beginning to unravel in or around 2010.

"Let me say this on the record, I had no reason to believe that Jeff Rubin was doing anything illegal or irresponsible or unethical," Drew Rosenhaus said. "We never had any inkling that he was ever dishonest. We never had a player come to us until this casino fell apart."

However, legal documents obtained by Y! Sports as well as interviews with multiple sources show Rosenhaus could have had reason to know Rubin , who graduated from the University of Florida with a degree in exercise and sport sciences in 1997 and began developing a relationship with Rosenhaus in 1999, had mismanaged client money as early as '03 – approximately five years before Rubin began recruiting players to invest in the bingo operation.

In an arbitration document filed with the NFLPA against Rosenhaus by attorney David Cornwell, suspended Rosenhaus Sports vice president Danny Martoe alleged he and former Rosenhaus client Barrett Green told Rosenhaus "in or around 2005" that Rubin had mismanaged Green's funds.

Green, an NFL linebacker for six years, confirmed Martoe's account when contacted by Y! Sports but said he and Martoe told Rosenhaus about Rubin's mismanagement two years earlier during his first contract with the Detroit Lions. Green said he hired Martoe to investigate why money was missing from his account. That investigation, two sources said, revealed the unauthorized transfer of two of Green's game checks into the account of two other players Rubin represented.

In the filing, Martoe said Green considered firing Rosenhaus for referring him to Rubin and telling the player Rubin was "trustworthy and competent."

Because Rosenhaus feared being fired by Green, he and Martoe discussed "the manner in which [Rubin] mismanaged Mr. Green's account" on multiple occasions, according to the filing. It was during those discussions Martoe said Rosenhaus "became impressed" with him and "encouraged [him] to come work with Rosenhaus Sports."

Martoe accepted Rosenhaus' offer and went to work for Rosenhaus Sports in or around 2005. Martoe now claims the firm owes him more than $1 million in commission and compensatory damages.

According to Martoe's claim, shortly after he joined Rosenhaus Sports, Rosenhaus directed him to "repair his relationship with [Rubin]," who had become "dissatisfied" with Martoe after he was fired by Green. Rosenhaus did so because Rubin, according to Martoe's filing, was "'very important to Rosenhaus Sports business."

Martoe objected to Rosenhaus' instruction, telling the agent he "did not trust Mr. Rubin," according to the filing.

Martoe declined further comment, Cornwell said.

Beyond the situation with Green, Rubin settled a claim for $40,000 in 2004 when one of his clients alleged several signatures on insurance documents executed in his name were not his. That claim – which Rubin did not deny – and the settlement are listed on the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority website.

Four years later, Rubin began recruiting players to invest in the failed Alabama bingo operation – an operation that was $41 million in debt when Rubin secured his first 12 NFL investors, according to investment documents obtained by Y! Sports. Ten of those initial investors were Rosenhaus clients.

Recruiting relationship in action

In early 2005, Owens was at the height of his career. He had just appeared in the Super Bowl with the Philadelphia Eagles and was a perennial Pro Bowler. Despite the success, he was in search of a new agent after deciding to fire agent David Joseph, who represented him for the first nine years of his career.

The decision wasn't one Owens took lightly.

Owens, who lost $2 million in the Alabama casino operation, described the rationale behind the split from Joseph in his self-titled book "T.O." The wide receiver said it was ultimately a review of his financial affairs that led him to believe he needed new representation.

When Owens and his friend of nearly 20 years, Theron Cooper, saw Rosenhaus walk into a celebrity bowling tournament in Miami, Owens said in the book he felt "fate was intervening." Owens urged Cooper to approach Rosenhaus to see if he'd be interested in representing the wide receiver.

After Cooper initiated a brief discussion between Rosenhaus and Owens, the parties agreed to have a formal meeting in Atlanta. It was at that meeting in a downtown Atlanta hotel that Owens and Cooper said Rosenhaus introduced them to Rubin, who they said Rosenhaus brought to the meeting unannounced. Former Rubin employee Peggy Lee confirmed that she attended the meeting with Rubin.

Owens and Cooper described a "joint presentation" between Rosenhaus and Rubin which was attended by multiple members of Rosenhaus' and Rubin's teams and lasted a little more than an hour. Both Owens and Cooper remember Rosenhaus emphatically endorsing Rubin to handle Owens' financial affairs.

"Drew said, 'If you're looking for a financial adviser, I recommend Jeff Rubin and Pro Sports Financial,' " Cooper told Y! Sports. "He told Terrell and I that he had referred a lot of his players to Rubin."

According to Owens, in a follow-up meeting at the wide receiver's Atlanta-area home a few days later between himself, Cooper, Rosenhaus and Rosenhaus employee Robert Bailey, Rosenhaus again urged Owens to hire Rubin.

"We recommend you use Jeff," Owens recalls Rosenhaus saying. "He handles our clients, we trust him."

When asked if Owens' recollection of how he met and began to work with Rubin was accurate, Rosenhaus declined comment. However, Rosenhaus was adamant that simultaneous meetings between himself, a financial adviser, and a player would not constitute cooperative recruiting. He was also adamant that he and his company don't endorse financial advisers to players.

But Owens said not only did Rosenhaus and Rubin cooperatively recruit him, Owens says he never would have signed with Rubin had it not been for Rosenhaus' repeated assurances that Rubin was the right man to handle Owens' financial affairs.

"I never knew who Jeff Rubin was before Drew introduced me to him," Owens said. "Drew was supposed to be the best agent, he's recommending Pro Sports Financial and they represent [a large number] of Rosenhaus clients, you think they must be the best too. Why wouldn't you want to go with the best?"

When asked if he felt that Rosenhaus shared in the responsibility for the losses players experienced with Rubin, Owens offered a measured response.

"Some of this is my fault because I had ultimate responsibility for my finances," said Owens, who was released by the Seattle Seahawks last week. "As a player without much understanding of the financial realm, we're easy prey. … How do you decipher who's good and who's bad?

"[But] with what I know now, Drew definitely needs to share in the responsibility. … Other players may not want to speak up out of loyalty to Drew but at the end of the day he bears some of the responsibility [for our losses] based on the referrals he was giving to [Rubin] and Pro Sports Financial.

"For someone to work as hard for their money as we do, to have it taken away by people we trust, who we find out later had other motives, it's a sick feeling."

Getting ahead and staying ahead

An NFL veteran player who spoke to Y! Sports on the condition of anonymity, said he was recruited simultaneously by Rosenhaus' and Rubin's companies in or around 2006, and that the firms had a cooperative recruiting relationship until at least 2008. The player was among those who lost money in the Alabama casino operation.

"[A Rosenhaus employee] came to see me and [a Rubin employee] was on the trip with him. They recruited together," the player said. A former Rubin employee confirmed the firms recruited prospective clients together during this time and that the direction to do so came from firm management.

"I would have loved to have known all the shady stuff that was going on with Jeff Rubin," the veteran player said. "That information would have changed things dramatically [in terms of allowing Rubin to manage my finances]. … To find this stuff out after the fact is disheartening. And that's part of the reason I fired Drew, because I had to question if he had my best interests in mind."

When asked about the player's claims, Rosenhaus said neither he nor anyone at his firm ever cooperatively recruited a prospective client with a financial adviser to the best of his knowledge.

"Not that I know of," Rosenhaus said.

Rosenhaus said agents and financial advisers are sometimes forced to meet with a player simultaneously in the recruiting process. Of five other agents surveyed, only one said he had ever experienced anything like that.

When asked if a player could construe a shared meeting as an endorsement by one party of the other, Jason Rosenhaus said: "The answer is no." Asked if Rosenhaus Sports' company policy allowed employees to communicate with financial advisers and if there were any parameters that governed those interactions, Drew Rosenhaus said his employees were allowed to communicate with financial advisers so long as they did not violate NFLPA regulations.

"We obviously expect them to operate at the same level that we do, and to the best of our knowledge they do, otherwise they wouldn't be working for us," Rosenhaus said.

When asked how a Rosenhaus employee and a Rubin employee could have ended up in front of a college player at the same time and leave the player with the impression they were collaboratively recruiting, Rosenhaus said it was likely a misunderstanding.

"We recruit so many players and take so many trips," Rosenhaus said. "Maybe guys are on the same flights coincidentally, or went to similar games and communicated with a financial adviser at a game."

But the player said the two firm's employees coming to see him at the same time was no coincidence. A Rosenhaus employee, the player said, "is the one who got me in touch with the guys at [Rubin's company,] Pro Sports Financial." He said he believed Rosenhaus was well aware of the arrangement.

"It's all about getting ahead and staying ahead for Drew … [he] definitely had to know what was going on," the player said. "Out of sight, out of mind, I guess. It was, 'Do what you've got to do to get the kid signed,' and Drew will do whatever it takes to sign players."

Warning signs

Aside from the allegations by Green and Martoe, Y! Sports identified numerous instances beginning in 2004 where accessible information – which didn't require consent or approval to uncover – might have provided material warning signs about Rubin's inability to safely manage his clients' finances.

September 2004 – A $119,000 complaint was filed against Rubin with FINRA by former NFL linebacker Johnny Rutledge. Rutledge alleged "several of his signatures on certain life insurance application documents [were] not his."

According to BrokerCheck – which is publicly available on the FINRA website and requires less than five minutes to access – Rubin and/or his firm settled the claim for $40,000 shortly after it was filed. They did so without either admitting or denying the allegations.

When asked if he was aware of this complaint against Rubin, Drew Rosenhaus said, "[T]his is the first I've ever heard of that."

• June 2005 – Rubin, 31 at the time, purchased a custom waterfront home in South Florida for $2.8 million. The home was in an area where at least four of Rubin’s clients also lived. He leased a Lamborghini for approximately $153,000 in 2008 and defaulted on the agreement in 2010. One former Rubin employee said Rubin was making upwards of $500,000 a year by '05.

"Your financial adviser shouldn't be living in the same neighborhood as his multimillion-dollar-earning clients," said Eric Pettus, a financial adviser who is working with former Rubin client Samari Rolle. "Even if he has a hundred clients, the percentage he should be making doesn't make him enough to be living in a new house in Lighthouse Point."

Mike McIntyre, a former Pro Sports Financial vice president of client services and longtime friend of Rubin's, said Rubin began leveraging clients for personal gain as early as 2001. In one instance, McIntyre says Rubin did so at Rosenhaus' suggestion.

"Back in the day, the company wasn't making that much money," McIntyre said in a June discussion with Y! Sports. "And … we were working a lot with Drew [who] really took a liking to me … [he] was like 'Mac, I want you to make more money. … 'You know what, I got this guy who's buying a house. Why don't you let Mac become a [real estate agent], have him get his real estate license? This way he can get a real office guy, make some extra money on the side. It doesn't take that much commitment and time to do both."

Rubin and McIntyre acted on Rosenhaus' suggestion and according to the Florida Department of Business Professional Regulation, McIntyre became officially licensed to sell real estate in April 2001.

"The way Jeff got his house is [through] Michael Friend, who was the builder in Lighthouse Point," McIntyre said. "[Friend] built Jevon's house and he built [Plaxico Burress'] house. So they kinda worked out a deal where commissions for those two houses brought down the price for Jeff's house."

Current Washington Redskins player Santana Moss and recently retired Redskins player Clinton Portis also bought homes from Friend, according to McIntyre. All four players purchased their homes between September 2005 and March 2006. Only Kearse still lives in his home full time. Burress' home was subject to foreclosure proceedings in 2010, and Moss and Portis left their homes, taking multimillion dollar losses.

An agent's primary responsibility

The NFLPA requires agents to act at all times in a fiduciary capacity on behalf of their clients to protect their best interests.

Timothy Davis, who co-authored the book "The Business of Sports Agents" with former NFLPA arbitrator Kenneth Shropshire, said, "[T]he relationship between an athlete and a sports agent is governed by the same legal principles as any other agent and principal relationship. The basic obligations that agents owe to their clients are defined not only by their contract but by the fiduciary characteristics of the relationship. As is true of other agency relationships, the agent and athlete relationship is subject to the duties that arise from the fiduciary duties imposed on the agent. The most fundamental fiduciary obligations imposed on the agent are the duties of undivided loyalty and good faith.

"Although fiduciary duties arise by operation of law, player association agent regulations acknowledge the fiduciary character of the relationship. For example, both the NFLPA and MLBPA agent regulations refer to the fiduciary character of the player/agent relationship."

When Rosenhaus and his brother Jason were asked if fiduciary duty required them to put the interests of their clients above their own they stated it did, at all times.

"Everything you do on behalf of your client, you've got to put their interests before what your own would be," Rosenhaus said. "We've always subscribed to that."

But numerous financial professionals who have worked with Rosenhaus and spoke with Y! Sports on the condition of anonymity said Rosenhaus and his employees consistently refused to make referrals to financial advisers who would not send them business in return. This practice continued long after it should have been clear that the reciprocal referral relationship they had with Rubin and his company had exposed their clients to risk.

"Drew's employees have said to me, 'Drew likes you, he thinks you do great work for the players, but he said we can't refer business to you because you don't refer business to us,' " one of the financial professionals said.

Another well-placed financial source said "I asked [a Rosenhaus sports employee] how come they don't refer clients to me and their response was 'because you don't recruit.' The inference was they wouldn't send me players because I didn't recruit to send players their way."

The Rosenhaus brothers declined to comment when asked if the financial professionals' claims were true.

In his arbitration filing with the NFLPA, Martoe said Rosenhaus sought more than a reciprocal referral relationship with some of the financial advisers they introduced to players. Martoe alleged he was told that if he introduced clients "like Dez Bryant and others" to a financial adviser at SunTrust bank, he would receive his commissions faster. That's because Rosenhaus' firm would get a "bigger loan and a better rate" from SunTrust, Martoe said.

While the Rosenhaus brothers declined to comment on whether they had ever referred a player to a specific financial adviser, citing the confidentiality of the NFLPA arbitration process, Drew Rosenhaus acknowledged they had given some players "a couple of names of guys that we think could possibly do a decent job for them."

When asked if referring a player to those financial advisers subjected them to a duty to investigate an adviser's credentials, Jason Rosenhaus said "the short answer is 'yes,' to a reasonable extent." When asked to define what "reasonable" efforts they would take to vet an adviser when making a referral, Jason Rosenhaus said it was "impossible" to do as "everything depends on a particular circumstance."

"I think that obviously it should be somebody that's registered with the NFLPA in good standing and who our clients speak highly of," Drew Rosenhaus said. "If our clients are happy with a financial adviser, that speaks well of [him]."

Asked if NFLPA registration was an endorsement of an adviser's skill, honesty or competence, the Rosenhaus brothers said it was not, it was merely a "minimum qualification." When asked if they were making "reasonable" efforts to refer clients to honest, ethical, and competent advisers by relying solely upon the "minimum qualification" of NFLPA registration and their clients' willingness to "speak well" of a given adviser, Drew Rosenhaus said "The biggest problem is, you can do a bunch of research on a financial planner, [he] could have great recommendations from players …. could be in good standing and then [he] goes off and does something … out of character. ....Anytime you recommend someone, that's a tough thing. I make sure to tell guys that I can't vouch for anybody but myself and Jason."

The NFLPA declined to comment on whether Rubin was ever registered in the NFLPA financial adviser program.

Asked if there was a heightened duty to conduct periodic due diligence on an adviser like Rubin who represented such a large number of Rosenhaus clients, the brothers said they were prohibited from doing so. It's unclear what rule or regulation they were citing as authority.

"Once a player has a relationship with a financial adviser, at that point, unless a player asks us to get involved, asks us to evaluate their financial investments, we can't," Drew Rosenhaus said. "There's nothing that we can do."

While the Rosenhauses reject the suggestion they shared in the responsibility for the losses their clients experienced in dealing with Jeff Rubin, they did shed some light on why they may have missed so many seemingly discoverable issues.

The Rosenhaus brothers didn't want to be fired.

"As long as [Rubin] didn't say to the guys we had with him, 'fire Drew,' we peacefully co-existed," said Jason Rosenhaus. "Our clients were mesmerized by this guy."

Asked if their concern for appeasing clients may have impacted their ability to represent the players' best interests, the Rosenhauses said they were as surprised as anyone by Rubin's fall.

"It's not something where we looked the other way and we knew what was going on," Jason Rosenhaus said. "We were shocked. Everybody was shocked."

"I guess the point I would make to you is … there are people who have to pay for this, and there are people who should be punished for it," Drew Rosenhaus said. "There are people who should be accountable, but Jason [Rosenhaus] and I are innocent victims, just like our clients."